Test-Driven Development: #6 Testing Alerts, Popups, and Messages

Now how do we test those pesky alerts?

Introduction

It's been a long time! Really happy that I have time to write about TDD again, and with an interesting topic from which we can know if our users had seen an alert, popups, or simply seen a message (toast) appearing to him

The Point?

How is this important, you ask?

Well, Imagine that our user is trying to log in but he is giving us an invalid email without him noticing, it would be nice to either show a message to him, saying that he missed a '@' in the email field

But what if after a couple of iterations over our app, and somewhere in version '1.4.3', this broke, and users no longer get a hint about why their email is not getting accepted, especially for an old user of our app, it might get irritating

However, if a test covers this; before we even launch any new version, this issue would be well on our issue tracker.

So this post we will cover how to cover such cases with a unit test coverage, and I think it would be interesting in showing how do I handle issues in my project in another post

Without further ado, let's get rolling 😎

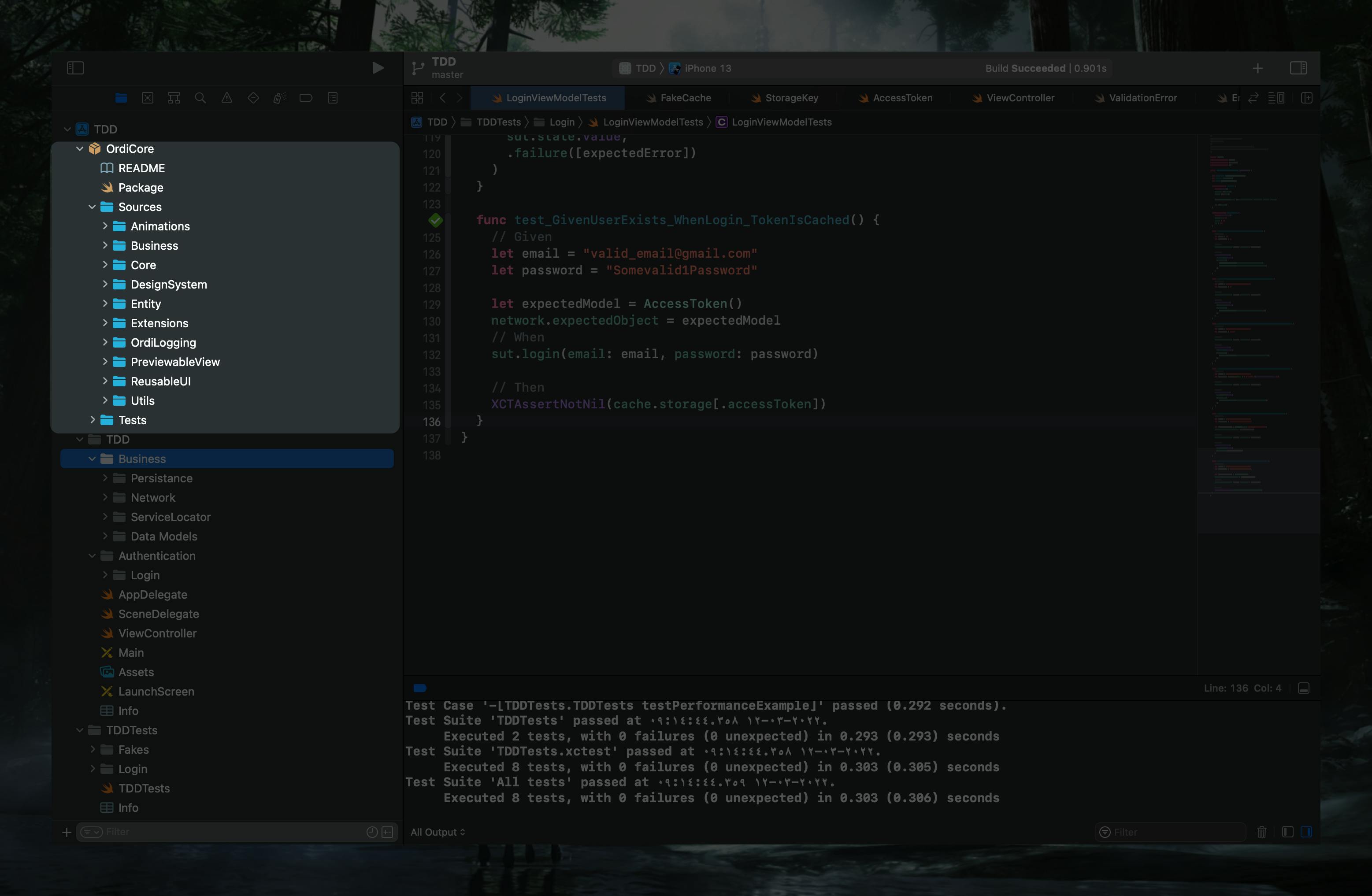

Revisiting the project after some changes

Remember that last demo video I put on the previous post of this series?

Well, I did promise you guys that I will make improvements to the refactoring and I did,

It now utilizes my open-source OrdiKit which is a fast way for me to put files I use from time to time, or just wanna test an idea or probably launch a project, it utilizes SwiftUI and UIKit

I don't want to spend much time on what went on in the Refactoring, but there is an interesting part I believe, which is called ServiceLocator

It's a pattern from Game Development and is a bit strange in iOS development as it uses Singletons

Before you throw any knives in the comments, let's take a step back and see why is this put here

If we think about Network and Cache, normally these are 2 dependencies where the app depends on

They shouldn't be repeated or recreated, in fact, that would create a problem if am tracking the progress of some network calls, or am storing 2 stuff simultaneously on the disk

So it makes sense to have this as a single instance inside the ServiceLocator.

Other than that, we're ready to go test our side-effects in form of alerts

If we return to our Testing file TDDTests/Login/LoginTests

We can add a test function like so…

func test_GivenInvalidEmail_WhenLogin_UserSeesAnAlert() {

// Given

let email = ""

let password = "Somevalid1Password"

// When

sut.login(email: email, password: password)

// Then

XCTAssertEqual(

router.routingAction,

RoutingAction.alert(ValidationError.empty(.email).errorDescription)

)

}

You will find that we want to have a new dependency called router, ideally the router would have its own state or action, so we can check if that action corresponds to what we want to verify, in our case, when the user forgets to pass his email, in such case we would want to show an alert (just for sake of simplicity for now), that he can’t leave his email blank

As of now, we don’t have such functionality so let’s start adding it to our production code

public typealias AlertAction = (title: String, style: UIAlertAction.Style, action: () -> Void)

public protocol RouterProtocol: AnyObject {

func present(_ view: UIViewController)

func startActivityIndicator()

func stopActivityIndicator()

func dismiss()

func pop(animated: Bool)

func popToRoot()

func popTo(vc: UIViewController)

func push(_ view: UIViewController)

func alertWithAction(

title: String?,

message: String?,

alertStyle: UIAlertController.Style,

actions: [AlertAction]

)

}

This is how our Routing functionality is going to provide, now let’s wait here and think what is going on

What we want, is an encapsulated access to our ViewController from the presentation layer, in our case, the LoginViewModel this encapsulation provides us with scoping to just the navigation functionality, so I can control the ViewController’s navigation from here, without having any access on the ViewController itself, let’s see how with extra details, by defining our Router Implementor

public final class Router: RouterProtocol {

private weak var presentedView: UIViewController!

init(_ view: UIViewController) {

presentedView = view

}

public func present(_ view: UIViewController) {

presentedView?.present(view, animated: true, completion: nil)

}

public func dismiss() {

presentedView?.dismiss(animated: true, completion: nil)

}

public func pop(animated: Bool) {

_ = presentedView?.navigationController?.popViewController(animated: animated)

}

public func popToRoot() {

_ = presentedView?.navigationController?.popToRootViewController(animated: true)

}

public func popTo(vc: UIViewController) {

_ = presentedView?.navigationController?.popToViewController(vc, animated: true)

}

public func push(_ view: UIViewController) {

presentedView?

.navigationController?

.pushViewController(view, animated: true)

}

public func alertWithAction(

title: String?,

message: String?,

alertStyle: UIAlertController.Style,

actions: [AlertAction]

) {

let alert = UIAlertController(title: title, message: message, preferredStyle: alertStyle)

actions.map { action in

UIAlertAction(title: action.title, style: action.style, handler: { (_) in

action.action()

})

}.forEach {

alert.addAction($0)

}

presentedView?.present(alert, animated: true)

}

}

Notice the private access modifier before the controller? Exactly what we’re looking for

Giving our ViewModel The Power of Navigation

If we get back to our ViewModel, we can now hand it a router by dependency injection, and have it show the view an alert when needed

...

var cancellables = Set<AnyCancellable>()

var router: RouterProtocol

init(router: RouterProtocol) {

self.router = router

}

...

func validate(_ email: String, _ password: String) {

...

guard !errors.isEmpty else { return }

state.send(.failure(errors))

router.alertWithAction(

title: "Validtion Errors",

message: errors.map { $0.text }.joined(separator: "\n"),

alertStyle: .actionSheet,

actions: [

(title: "Ok", style: .default, action: { })

]

)

}

If we ran and tested our code…

Voilà

Faking our Router until we make it

Now comes our testing code’s turn

First, we need to create a FakeRouter that gives us information about the navigation state

In order for us to have access to our navigation stack, we need to define a state enum, which holds the actions given to the router

enum RoutingAction: Equatable {

case present(_ vc: UIViewController.Type)

case push(_ vc: UIViewController.Type)

case dismiss

case pop

case popToRoot

case popToVC

case popTo(_ vc: UIViewController.Type)

case alertWithAction((title: String, message: String))

static public func ==(lhs: RoutingAction, rhs: RoutingAction) -> Bool {

switch (lhs, rhs) {

case let (.popTo(a), .popTo(b)): return a == b

case let (.present(a), .present(b)): return a == b

case let (.push(a), .push(b)): return a == b

case let (.alertWithAction(a), .alertWithAction(b)):

return a.title == b.title && a.message == b.message

case (.dismiss, .dismiss),

(.pop, .pop),

(.popToRoot, .popToRoot),

(.popToVC, .popToVC):

return true

default:

return false

}

}

}

This way, we can have an in-memory storage that we can use it later on, to test against whether the user did present a view, did push to a view, or simply gave an alert

And to wrap it up so we can continue on with testing…

final class FakeRouter: RouterProtocol {

var actions: [RoutingAction] = []

var alertActions: [AlertAction] = []

func popToRoot() {

actions.append(.popToRoot)

}

func popTo(vc: UIViewController) {

actions.append(.popToVC)

}

func push(_ view: UIViewController) {

actions.append(.push(type(of: view)))

}

func present(_ view: UIViewController) {

actions.append(.present(type(of: view)))

}

func dismiss() {

self.actions.append(.dismiss)

}

func alertWithAction(

title: String?,

message: String?,

alertStyle: UIAlertController.Style,

actions: [AlertAction]

) {

self.actions.append(.alertWithAction((title ?? "", message ?? "")))

self.alertActions.append(contentsOf: actions)

}

func pop(animated: Bool) {

self.actions.append(.pop)

}

}

Notice how we append the type to the actions array?, similar to our FakeCache, we just register it until the test has run, so we can later on test against if it indeed has a certain action that we expect it to be, or not.

Back to our tests, now we need to supply our SUT with a FakeRouter so we can test it

Wrapping it up

class LoginViewModelTests: XCTestCase {

var network: FakeNetworkManager!

var cache: FakeCache!

var router: FakeRouter! // <- Changed

var sut: LoginViewModel!

override func setUp() {

super.setUp()

network = .init()

cache = .init()

router = .init() // <- Changed

ServiceLocator.main = .init(network: network, cache: cache)

sut = .init(router: router) // <- Changed

}

override func tearDown() {

super.tearDown()

network = nil

cache = nil

router = nil // <- Changed

sut = nil

}

Now that our LoginViewModel knows how to use our FakeRouter, let’s fix some of our test code below

func test_GivenInvalidEmail_WhenLogin_UserSeesAnAlert() {

// Given

let email = ""

let password = "Somevalid1Password"

// When

sut.login(email: email, password: password)

// Then

XCTAssertEqual(

router.actions,

[

RoutingAction.alertWithAction((

title: "Validation Errors",

message: "Email can't be empty"

))

]

)

}

And that’s it!

Conclusion

Now that we have a way of testing our Alerts, Popups, and Messages… or simply what I like to call them, Async Views, where a view cuts through the flow for the user to take an action then return to the normal flow We can now go to our next stop which is testing the our navigation flow, which by now you can guess how it really can be easy

Tell you what, how about you try to implement this on your own? You will be amazed by how easy it is now to test your navigation, and next stop we will go over it quickly and talk about something really important, which by now, the ViewModel became somewhat big, so let’s talk about how we can dissect it even further, so we can avoid going from ‘MVC’ to ‘MVVM’ (aka, massive view controller, to massive view model) 😉

And if you’re an eager one and wants to know our progress on Github, feel free to see the code here